Week 7: Italy

- kelafoy

- Sep 26, 2022

- 15 min read

Updated: Oct 2, 2022

Introduction

“Variety is the spice of life, and like Indian cuisine, Italian cuisine is renowned for its regional variety. Many cooking methods get their names from the region they belong to. Even dishes are usually characteristic to a specific region, and some have spread across the country to become not only national, but also international favourites. Lasagne, bolognese, fettuccine, tiramisu, margherita, gelato… These are all names that bring mouth-watering thoughts to any Italian food lover's mind. But ever heard of alla caprese or battuto? These terms refer to Italian cooking methods that are used to make some of these lip-smacking dishes.” (Arora, 2016)

Method of Cookery:

“Buy the best ingredients:

Italian food is relatively simple; its success is based mainly on the flavour of the key ingredient, so this must be the highest quality. The Italians spend far more on food than the British, in spite of having a smaller income. According to a 2008 Washington State University survey, the Italians spend $5,200 (£3,600) per person per year on food, while the British spend $3,700 (£2,600) – lower than the Germans, French, Spaniards, and most other Europeans. To emulate an Italian in the kitchen, you need to prioritize flavour.

Use the right pan:

What difference could a pan make to the final result? Well, a risotto made in a paella pan would never have the soft gluey quality of a good risotto. A sauté pan, because of its depth and curved sides, is better for braising meat or vegetables than a frying pan. Pasta should be cooked in a cylindrical pot, so the water returns to the boil more quickly once you have added the pasta, preventing the shapes from sticking together. Ragu, stews, and pulses are cooked in pots made of earthenware, the best material for slow cooking, because it distributes the heat evenly.

Season during cooking:

Pepper is not used a lot in traditional Italian cooking, but, when it is, it’s usually added during – not after – cooking. Salt, always sea salt, is added as a dish cooks, usually at the beginning, so it dissolves properly, which means less call for serving salt.

Use herbs and spices subtly:

Both are added to enhance the flavour of the main ingredient, not to distract from it. Pellegrino Artusi, one of the great cookery writers, wrote that flavourings should not be detected; they should only be a gentle foil. Chili, nowadays the most popular, was once used only used in Calabria and the province of Siena. It is added in moderation mainly to shellfish and some tomato sauces. Nutmeg is often added to mashed potatoes and meatballs; cinnamon to braised meat, custard and cakes, and cloves always go into stock, chickpeas, and game. Flat-leaf parsley, rosemary, sage, and basil are invariably used fresh, but oregano is always used dried.

Make a good battuto:

A battuto is a mixture of very finely chopped ingredients and varies according to their use. The most common battuto is onion, carrot and celery, which is the basis of the soffritto (see Commandment 6), but there are battuti of other ingredients, too. Some battuti are used a crudo, which means that they are added to the main dish without being cooked before. The most common of these is that of parsley, garlic, capers or olives and a touch of chili; it is used for dressing cooked vegetables, such as cauliflower, on boiled fish or with boiled meat, tongue or ham. Traditionally, onion and garlic are never present in the same battuto.

Keep an eye on your soffritto:

A soffritto is a cooked battuto, mostly a mixture of pancetta or lardo and vegetables. It is a vital part of many Italian dishes. A soffritto must be watched and stirred with care while it is cooking. Two minutes longer watching the telly and your soffritto becomes a burnt mess. I always add a pinch of salt when I sauté the onion (usually the first ingredient to go into the pan), because the salt releases the liquid in the onion, thus preventing it from burning.

Use the right amount of sauce:

The Italians like to eat pasta dressed with sauce – not sauce dressed with pasta. The usual amount of sauce added to a portion of pasta is two full tablespoons, so the amount of ragu necessary for dressing about 500g of pasta is made with 400g of meat, plus the pancetta, all the vegetables for the soffritto and the tomatoes. A tomato sauce for 400-500g of spaghetti is made with 1kg of fresh tomatoes or with two tins of plum tomatoes.

Taste while you cook:

Food in Italy is mostly cooked directly on the heat and not in the oven – which might be why the Italians are not strong on baking. The food in the pot is nurtured all through the cooking: a spoonful of water or wine may be added, a pinch of salt, a grinding of pepper, a touch more of chili, a teaspoon of sugar, a drop or two of lemon juice or vinegar may all go in the pot. The cook is perpetually tasting and adjusting. The final result is a labour of patience and love.

Serve pasta and risotto alone:

I shall always remember a lunch at our house when my husband, a very reserved English man, categorically responded to one of my cookery colleagues who asked for the salad with her penne: “No, I am sorry, you are in an Italian home, and you can’t have salad with pasta.” That’s it. Neither pasta nor risotto are ever served with salad, vegetables, meat or fish or anything. Only one pasta dish and two risotti are traditionally accompanied by meat: Carne alla Genovese – a braised beef dish allegedly brought to Naples by the Genovese merchants, served with penne; Ossobuco alla Milanese – the traditional ossobuco without tomatoes served with saffron risotto; and Costolette del Priore – breaded veal chops in a cheese sauce, served with risotto in bianco (plain risotto).

Don’t overdo the parmesan:

There may be a bowl of grated parmigiano reggiano on the table when pasta or risotto are served, but the usual amount added is not more than 1-2 teaspoons, so as not to overpower the flavour of the main dish. It should be grated, not flaked; except on special salads, such as those with fennel or artichoke. The cheese must dissolve, imparting an overall flavour like a seasoning. Parmesan is not added to fish or seafood risotto, apart from some varieties with prawns.” (Del Conte, 2016)

Prior Knowledge of the Dish:

I have known of the five mother sauces throughout most of my cooking career. I perfected my tomato sauce…also known as red sauce or gravy…by the time I was 25 years old in the tiny kitchen of my 2-bedroom apartment while teaching myself to cook. It has become such a favorite in my household that my daughter requests it every year for her birthday dinner. I love a creamy bechamel to use as a base for mornay (cheese sauce) in mac-n-cheese. And there’s nothing like a good hollandaise to top eggs benedict for a tasty brunch. Provided the hollandaise sauce doesn’t break, of course. 😉 I think most of us are partial to Italian cooking because it is an easier way to learn to develop flavors before moving on to more complex cuisines from around the world. Besides…who doesn’t love a big bowl of carbs (pasta)? 😊 I don’t use the blonde velouté sauce much or the brown espagnole sauce, primarily due to not having the stock bases on hand that are required for each of them. The velouté starts with a chicken or fish stock on most occasions, and the espagnole base begins with a beef or veal stock. Having an onion allergy requires me to make my stocks from scratch since most canned stocks and broths are pre-seasoned and include onion juice or onion powder. It's just not very cost effective for me to make my own stock. It tends to spoil before I can use it all.

Learning Objectives:

1. Introduce the history of Italy, its geography, cultural influences, and climate.

2. Introduce Italian culinary culture, its regional differences, and dining etiquette.

3. Reveal how this peasant cuisine became a great Mother cuisine, and the influences of the Silk Road on it.

4. Discuss Italian dry and fresh pastas, Italian produce, and tomatoes.

5. Identify the foods, flavor foundations, seasoning devices, and favored cooking techniques.

6. Teach the unforgettable, important techniques and dishes of Italy

Background Information

Origin & History:

“The Romans loved feasting on food: the banquet was not simply a moment of social conviviality, but also the place where new dishes were served and tried. The Empire embraced the flavors and ingredients of many of the lands it had conquered: spices from the Middle East, fish from the shores of the Mediterranea, and cereals from the fertile plains of North Africa; Imperial Rome was the ultimate fusion cuisine hot spot. The Romans, though, contrarily to how we’re today, liked complex, intricated flavors and their dishes often required sophisticated preparation techniques. Ostrich meat, fish sauces, roasted game, all watered by liters of red wine mixed with honey and water, never failed to appear on the table of Rome’s rich and famous.

Different was the culinary passage into the Middle Ages of Sicily which, since the 9th century, had become an Arabic colony: islanders embraced the exotic habits and tastes of their colonizers, a fact mirrored also in their cuisine. Spices and dried fruit became a common concoction and are still often found in Sicilian dishes. Many may not know that dried pasta, today a quintessentially Italian thing, was brought to the country, specifically to Sicily, by the Arabs, who appreciated the fact it was easy to carry and preserve, hence perfect for long sea trips and sieges. From the ports of Sicily, dried pasta made its way to those of Naples and Genoa, as well as France and Spain. So, contrary to what we hear often when talking about the history of pasta, it wasn’t Marco Polo that brought noodles to Italian shores. This is how, we can truly say, an Italian legend was born.

After Constantine declared Christianity a legal religion of the Empire and especially after it became the sole Imperial religion with the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, under the reign of emperor Theodosius I, Christianity began exercising heavy regulations upon people’s behaviors and habits, including the way they ate. Very much up to the year 1000, the monks of Italy (and of the whole of Europe, as a matter of fact) ate a strict diet of bread and legumes, with very spare additions of cheese and eggs on allowed days, along with some seasonal fruit. The meat was considered a dangerous aliment not only for its symbolic meaning: it was refused as food both because its production involved an act of blatant violence, the killing of an animal, but also because it was considered an energetic food, which could provoke in its consumer’s unclean desires and passions. In other words, Medieval Christians thought, meat could make you lose your chastity more easily than salad.

The Crusades had opened up Europe to the idea of communicating with one’s neighbor and products began to circulate with much ease: a new social class, that of merchants was born. It is, then, among this crafts and commerce crowd that the pleasure of good food became, once again, a symbol of social and economic status. Cooking returned to be a matter of enjoyment and refinement, a voyage among flavors and combinations. Meats and vegetables were once again roasted and braised, the old art of stewing and dressing dishes in rich, flavorsome sauces was rediscovered.” (Bezzone, 2019)

Methods Used:

“1. Alla Bolognese

This refers to the way in which a meat-based tomato and vegetable sauce that is cooked for several hours over low heat. The traditional ingredients added are onion, celery, and carrot with some minced meat. Red wine is added and cream or milk seals the sauce’s unique flavour. Originating in the Bolognese region, this sauce is usually served with flat pasta shapes such as tagliatelle or fettuccine.

2. Al Dente

‘To the teeth’ is the literal meaning of al dente which refers to a way of cooking pasta. Perhaps undercooking is a better word! If a pasta dish is going to be cooked once again, the pasta is usually cooked al dente the first time. This means when you bite it, it feels firm to the teeth and not soft. It is sometimes also used to refer to the way in which vegetables are cooked.

3. Risotto

Most Italians cook their rice in this way. If you want to make a risotto, all you have to do is sauté some short-grain rice in olive oil and add a meat stock to the rice to cook it. The rice is usually cooked without a lid, and each time the stock is absorbed, the rice is stirred and more stock is added. It is usually garnished with cheese or butter and eaten with meat. Sometimes pasta can be cooked in this way too.

4. Polenta

What the Romans enjoyed as porridge is now enjoyed by Italian food lovers as a versatile dish. This refers to the method of cooking a cereal such as cornmeal, buckwheat, or semolina in water for about an hour. Chickpeas can also be used. Once it is ready, it can be served as is with an accompaniment, or it can be baked, fried or grilled. Side dishes and additions to this preparation vary: everything from fresh herbs, roasted garlic to fish sauce and sausages.

5. Al Forno

Italians love to cook their pastas and pizzas ‘al forno’ which means ‘in the oven.’ Although this term applies to any oven nowadays, the traditional wood-burning oven or open flame grill was and is sometimes still used to cook dishes al forno.

6. Alla Caprese

Mozarella, olive oil, basil and tomato are staples at the heart of this cooking method which originated in Capri. These ingredients combined together are served as antipasto or a starter. These versatile ingredients are also combined to prepare a variety of pastas and dishes such as fusilli alla caprese and spaghetti alla caprese.

7. Alla Mattone

Mattone literally means a heavy brick or tile, and this cooking method gets its name from the brick that’s used to apply pressure to anything being cooked, especially for grilling or sautéing. Chicken or any other meat is a typical example of an ingredient that’s cooked in this manner.

8. Alla Genovese (Pesto)

Pesto is synonymous with alla Genovese which refers to the method of pounding or crushing olive oil, basil, pine nuts and garlic to make a sauce. The method originated in Genoa and a mortar and pestle are used to crush or pound the ingredients. There are other variations of this, for example pesto rosso uses tomato and almonds.

9. Battuto

In Italian, battuto means to ‘beat’ or ‘strike’ and refers to the method of finely chopping onions, celery, carrots, parsley, and some meat like bacon which are then cooked in fat, usually olive oil or lard. It forms the flavour base of many Italian pastas, risottos, and soups.

10. Crudo

Meaning ‘raw’ in Italian, the method refers to slicing seafood, usually fish, very thinly and topping it with olive oil, salt, and citrus juice. You’ll find this served in Italian fishing towns. It can also refer to a mixture of raw herbs and vegetables chopped together and added to a cooked dish just before it is served.” (Arora, 2016)

Dish Variations:

“Italian cuisine is strongly influenced by local history and traditions, as well as by the local and seasonal availability of products. Each region of Italy has its own regional food specialties. These regional differences are based on a combination of climatic factors (availability of specific ingredients), historic factors (migration flows, influence from other peoples), geographical factors (living by the seaside or in the mountains) and economic factors (gastronomy influenced by the presence of former noble courts, labor or peasant communities). Some of Italy’s most famous gourmet foods, which have gained international fame, such as white truffles, can actually be found only in specific areas of Italy.

While many countries have local culinary styles that differ from region to region, in Italy these differences are much more pronounced. This is not surprising considering the shape of the country – long and narrow, surrounded by the sea and with big mountains in the North. Add to that the fact that Italy became a unified nation only in 1861, after having mainly been a confederation of states for the previous thousand years, and this diversity becomes even more obvious.

This being said, the Italian menu is typically structured in much the same way all over Italy, with an antipasto, primo, secondo and dessert. Typical Italian foods and dishes include assorted appetizers (antipasti misti), all types of pasta, risotto and pizza, soups (minestroni and zuppe) and delicious meat and fish dishes. The main regional differences are in the sources of carbohydrates, the origin of the proteins and the choice of vegetables or contorni (side dishes).

To simplify grossly, we could say that in the North carbohydrates come mainly in the form of rice (the typical risotto comes from the Padana plane where large rise fields can be found around the Po River), polenta and potatoes, while in the South the main source of carbohydrates are the traditional pasta and pizza. Polenta is also a common dish in center-south regions, like Molise, though. Grains like orzo (barley) and farro (spelt) are eaten in various regions of Italy. Then there is also the focaccia, with several versions according to the region. So, even the most popular Italian foods are not necessarily common all over Italy. Note that there is a great difference between dishes that are generally considered as “typically Italian” abroad, but that may not be so widespread in Italy, and dishes that are popular in various regions of Italy, but relatively unknown abroad.” (Slow Italy, 2022)

References

“Do You Know These 10 Italian Cooking Methods?” Sid Arora. https://yourstory.com/mystory/8926a21d4d-do-you-know-these-10-italian-cooking-methods-/amp. 16 June 2016.

“Popular foods of Italy: 40 Iconic Italian dishes and must-try Italian foods.” Slow Italy. http://slowitaly.yourguidetoitaly.com/popular-foods-of-italy/. 2022.

“Ten Commandments of Italian Cooking.” Anna Del Conte. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/may/16/ten-commandments-of-italian-cooking. 16 May 2016.

“The History of Italian Cuisine I.” Francesca Bezzone. https://lifeinitaly.com/the-history-of-italian-cuisine-i/. 30 October 2019.

Dish Production Components

Recipes:

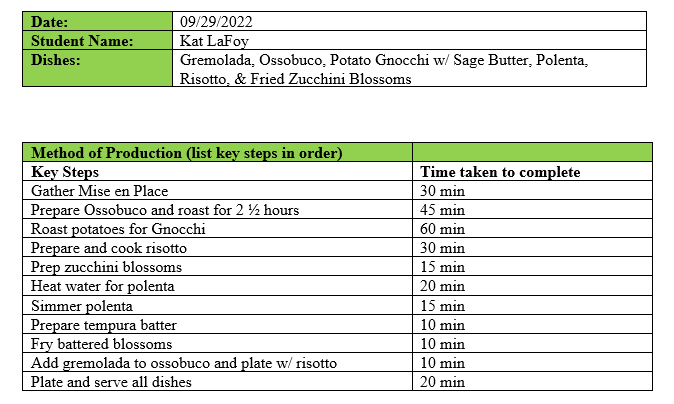

Plan of Work:

Sources:

Reflection & Summary of Results

What Happened(?): We showcased dishes from Italy this week. Every dish was part of a big collaboration to create one complete Italian dinner. We had one group working on potato gnocchi with sage butter, as well as tempura fried zucchini and tempura fried eggplant. Another group created the ossobuco and gremolada to accompany it. My group made the polenta and risotto.

Evaluation: The gnocchi was beautiful, but unfortunately it wasn’t cooked before plates-up at 1:00pm. I would have loved to see the finished product for this dish. The same group made a tempura batter and deep-fried zucchini as well as eggplant. The original plan was to tempura fry zucchini blossoms, but we are having supply chain issues just like the rest of the nation.

I gave them the focaccia recipe I like to use and they made fresh bread with a balsamic olive oil mixture for everyone to have with our meal.

The Ossobuco (veal shanks) looked and tasted AMAZING!!! It was paired with the risotto made by my lab partner, Sophia. You’ll have to wait until the end to see the final plating on that tasty dish. 😉

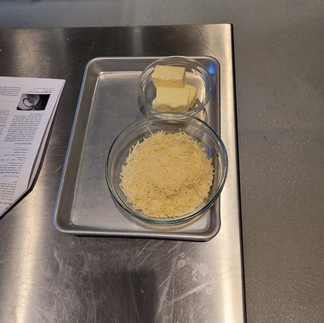

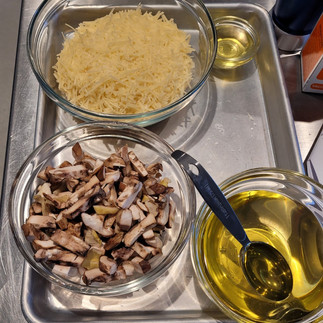

As stated earlier, Sophia and I had Risotto and Polenta this week. The risotto called for chicken stock and onion. Since I am highly allergic to onions, Sophia and I made a few substitutions. We replaced the chopped onion with chopped fennel. Since most stocks have onion in them, I made a vegetable stock using random ingredients I found in the lab (fennel root and fronds/carrots/eggplant/garlic/red bell pepper/mushrooms/fresh basil/peppercorns/soy/salt). The clarity and flavor were perfect. You could drink it like a tea. Not only did Sophia use it in the risotto, but Will made a separate veal shank (ossobuco) for me that was onion free using the stock I made.

The tricky part of the Polenta was getting the correct consistency, which I did using the veggie stock. It sat for a while waiting on the remaining dishes to be complete and started to congeal. “Polenta mixture should still be slightly loose. When polenta is too thick to whisk, stir with a wooden spoon. Polenta is done when texture is creamy, and the individual grains are tender.” (John, 2022) You can also help develop the creamy texture by stirring butter or olive oil into your polenta. By using the vegetable stock, it loosened the polenta and allowed the grains to separate from each other. This gave it the proper texture rather than it taking the shape of the bowl and becoming a block.

Conclusions: I depended on Sophia to do the actual cooking of the risotto this week. I have been having an off week, and I didn’t want to do a disservice to our dish. Especially since the rest of the class was depending on it for their dishes. She did an excellent job of getting the risotto to the right consistency without it being too thick. “One of the surest ways to ruin risotto is overcooking. Don't stress about constantly stirring risotto. It's much better to stir once every 30 seconds and trust the cooking process to do its thing. Over-stirring is one way to quickly ruin a risotto's texture.” (Nieset, 2022) We decided to add mushrooms to our risotto as well to give it that earthly umami that so many starch dishes are lacking.

Here is the complete dish using the Ossobuco and Gremolada made by Will, Natasha, & Celine, atop the Risotto, cooked by Sophia. The sauce and risotto were both made using the vegetable stock I created. It's so awesome seeing what can be accomplished with great teamwork. How every bolt in the machine has a function, no matter how insignificant it may seem.

Trying to find things to do when your part of the meal takes the least amount of time can be tough at times. Sophia and I were trying to think of something that would fit our Italian menu when a brilliant idea came to her. She got a recipe from her significant other for crepes…or crespelle in this case. "Crespelle are thin, soft sort of crêpe, which you can fill with your favorite sweet or savory ingredients." (Ubaldi, 2020) While Sophia was cooking the crespelle on the stove I was building the filling using goat cheese, honey, and fresh squeezed lemon juice. The crespelle were topped with powdered sugar and lemon zest before serving. This was the absolute best part of my day. Out of everything we made today, our crespelle dish was my favorite.

😊 I bet now you wish it was possible to taste a photo!

We'll be taking a break during Week 8 for our Fall Break at the university. Check back in for Week 9 as we take off for Spain! Metaphorically speaking of course. 😊

References

“7 Mistakes We've All Made When Cooking Risotto.” Lane Nieset. https://www.foodandwine.com/how/risotto-mistakes-avoid-from-italian-chef. 25 September 2022.

“How to Make Perfect Polenta.” Chef John. https://www.allrecipes.com/recipe/234933/how-to-make-perfect-polenta/#:~:text=Polenta%20mixture%20should%20still%20be,the%20individual%20grains%20are%20tender. 2022.

"How to Make Sweet or Savory Crespelle." Giulia Ubaldi. https://www.lacucinaitaliana.com/italian-food/how-to-cook/how-to-make-sweet-or-savory-crespelle?refresh_ce=. 27 July 2020.

Comments