China: History of Contribution To the Culinary World

- kelafoy

- Aug 24, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 31, 2022

Introduction

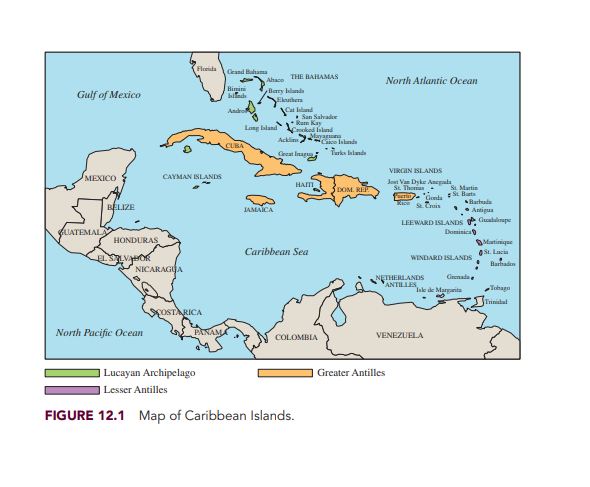

This week we are learning the history and origins of the culinary world in China. Based on our textbook, “The Five Elements described relationships between phenomena, and between foods. Fire, earth, metal, water, and wood connected to five tastes: fire–bitter, earth–sweet, metal–spicy and pungent, water–salty, and wood–sour. Cooks and doctors consider all five when planning a balanced dish or menu. A balancing of yin-yang and the Five Elements affected all aspects of Chinese life, from Chinese medicine, feng shui, the martial arts, military strategy, and the I Ching to Chinese culinary culture.

Through the fourteenth century, the Silk Road promoted an unprecedented sharing of ideas, arts, sciences, innovations, cooking techniques, and foods like onions, dates, figs, olives, oranges, apples, grapes, spices and herbs, tea, salt, potatoes, melons, sesame seed, walnuts, almonds, carrots, cucumbers, peanuts, wheat, chickens, and pomegranates.” (Allen, 2014)

Method of Cookery:

“Chinese cooking involves looking at the combination of the ingredients as well as paying particular attention to the complex process and equipment involved. Different ingredients are cooked using different methods, while the same ingredient can be used in different dishes to provide different flavors and appearances. There are hundreds of cooking methods in China. However, the most common methods are stir-frying, deep-frying, shallow-frying, braising, boiling, steaming, and roasting.” (Travel China Guide, 2019)

Prior Knowledge of the Dish:

My only familiarity with Chinese cuisine is my consumption of the Americanized versions sold in the United States. I am really excited to learn of the history of the foods and spices they use in the Chinese culture, as well as the reasons behind the flavor profiles. Out textbook touches on how “Chef and writer Barbara Tropp has observed how the Chinese dualistic philosophy of yin (dark and yielding) and yang (light and firm) are deeply fundamental to Chinese culture and cuisine. Chinese people know that successfully blending these opposites results in balance and harmony. Chinese cooks, from a humble street cook and the home cook to the restaurant chef, have the knowledge of yin and yang bred into them. Working intuitively with this concept, Chinese cooks incorporate it into every meal, whether they’re aware of it or not.” (Allen, 2014)

Learning Objectives:

· Introduce the history of China, its geography, far-reaching philosophical, religious, and

cultural influences, and its climate.

· Discuss the importance of the Silk Road, how it connected China across continents to the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and Rome, and its effects on Chinese cuisine.

· Introduce China’s culinary culture, four main regional cuisines, and dining etiquette.

· Identify Chinese foods, flavor foundations, seasoning devices, and famous cooking techniques.

· Teach by technique and recipes the major dishes of China.

Background Information

Origin & History:

“The art of Chinese cooking has been developed and refined over many centuries. Emperor Fuxi taught people to fish, hunt, grow crops and to cook twenty centuries before Christ. However, cooking could not be considered an art until the Chou Dynasty (1122-249 B.C.).

The two dominant philosophies of the Chinese culture are Confucianism and Taoism. Each influenced the course of Chinese history and the development of the culinary arts. Confucianism concerned itself with the art of cooking and placed great emphasis on the enjoyment of life.

Taoism was responsible for the development of the hygienic aspects of food and cooking. The principle objectives of this philosophy were people's wish for longevity. In contrast to supporters of Confucianism who were interested in the taste, texture and appearance, Taoists were concerned with the life-giving attributes of various foods.” (CCTV.com, 2003)

Methods Used:

“Unlike the majority of eastern cuisines most Chinese dishes are low-calorie and low-fat. Food is cooked using poly-unsaturated oils; milk, cream, butter, and cheese are not a part of the daily diet. Animal fats are kept to a minimum due to the small portions of meats used.”

(CCTV.com, 2003)

Dish Variations:

“By the time of Yuan Dynasty, China received first contacts with the west, bringing for the first-time access to many foreign food ingredients and methods of food preparation. This influence grew even more strongly during Ming dynasty (1368–1644) when trading with the rest of the world became much easier with the establishment of sea trading roots. By then, China gained access to many new plants, animal, food crops, and goods, including the food that was originally found only in the newly discovered “New World” (sweet potatoes, peanuts, maize, and many others).

In recent history, founding of People's Republic of China brought several changes of the cuisine that were both fueled by government efforts and created by minorities and western influence. In general, modern Chinese cuisine can be separated using two different schools of food. “Four Schools” refer to the cooking traditions of Shandong, Su, Cantonese and Sichuan, while the four additional cuisines developed in the territories of Hunan, Fujian, Anhui and Zhejiang. They all produce incredible variety of food based on rice, noodles, wheat, soybeans, herbs, seasonings and vegetables.” (Chinese Food History, 2022)

References

Allen, N. K. 2014. Discovering Global Cuisines, Traditional Flavors and Techniques. Chapter 1. Pearson.

“Chinese Cooking Methods.” https://www.travelchinaguide.com/tour/food/chinese-cooking/methods.htm#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20most%20common%20methods,%2C%20boiling%2C%20steaming%20and%20roasting.&text=The%20most%20frequently%20used%20method,used%20as%20the%20heat%20conductor. 28 October 2049.

“History of Chinese Cooking.” CCTV.com. http://www.china.org.cn/english/travel/53611.htm#:~:text=The%20art%20of%20Chinese%20cooking,(1122%EF%BC%8D249%20B.C.). 15 January 2003.

“History of Chinese Food”. http://www.chinesefoodhistory.com/. 2022.

Dish Production Components

Recipes:

Plan of Work:

Sources:

Reflection & Summary of Results

What Happened(?):

This week was our first opportunity to work in the new Tony & Libba Rane Culinary Science Center and let me tell you…IT WAS AWESOME!!! We have finally grown up from our 1960s home economics kitchen in Spidle Hall to state-of-the-art everything. Don’t get me wrong, I loved Spidle. However, it sure is nice having access to current technology and equipment.

Our focus this week is on China. We learned various things about the history of the cuisine and how Chinese philosophy influenced foods throughout the country. Per our usual, we split into groups and each group focused on one recipe from the assigned list for the week. Here are some amazing photos of my classmates at work and their wonderful dishes.

Evaluation:

My partner AP and I created the Szechuan Hot & Sour Soup. We had to tweak the recipe a little and make a few adjustments. I was told the result was outstanding. Of course, I couldn’t taste it. The chicken stock we used had onion in it, which kept me from being able to critique my own dish. Thankfully AP was able to tell me what she thought regarding the flavors, and we adjusted from there.

Conclusions:

It was missing that nice umami (savory characteristic found in broth) flavor and lacked a little of the mouthfeel that extra fat provides. We considered adding more tamari (higher in protein than soy sauce) to help with the umami, but we were concerned the salinity would be overpowering. “Although there are several benefits to using tamari sauce, there are some drawbacks as well, and one of the biggest considerations is the sodium content. While your body needs a small amount of sodium to function and thrive, filling up on too many high-sodium foods can negatively affect health.” (Link, 2018) Instead, we doubled the prosciutto which gave the soup an extra kick of salt as well as melted down the fat for a nicer texture in each bite. The dish seemed a little bland, so we also added about two tablespoons of fish sauce and sliced up one fresh Szechuan pepper and placed it in the pot for an added kick of spice. These small changes resulted in BIG flavor. 😊 All in all, I think this week was a great success.

The soup looked awfully monochromatic when finished. It was just a blah brown. “Eating involves more than just taste. It is a full sensory experience. Both food scientists and chefs will tell you that the smell, sound, feel, and, yes, the sight of your food are just as important as taste to fully appreciate what you eat.” (Rohrig, 2015) Garnishing with sliced green onions and Szechuan peppers made it a more beautiful and visually appetizing dish.

I sssssooooo wish I could have tried it myself. Take a look below and tell me what you think. Would you try it?

References

“Eating with Your Eyes: The Chemistry of Food Colorings.” Brian Rohrig. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/resources/highschool/chemmatters/past-issues/2015-2016/october-2015/food-colorings.html. October 2015.

“Tamari: Healthier, Gluten-Free Soy Sauce Substitute or Just Another Sodium-Filled Condiment?” Rachael Link, MS, RD. https://draxe.com/nutrition/tamari/. 13 August 2018.

Comments